Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apache: A Tale of Resistance and Perseverance

This article delves into the life of Geronimo, the legendary Chiricahua Apache warrior and leader. It explores his fierce resistance against Mexican and U.S. forces during the Apache Wars, highlighting key events, his remarkable skills, and the cunning tactics that earned him a reputation as a fearless and resourceful fighter. Discover the hardships Geronimo faced, his eventual surrender, and the impact of his legacy on both Native American history and American culture.

The Bascom Affair: The Start of the Apache Wars

Nothing is known of Cochise’s birth or early life. In the mid-19th century, Chief Cochise led the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache, indigenous to the Chiricahua Mountains. A natural leader, Cochise developed his skills under the mentorship of his father-in-law, Chief Mangas Coloradas, who was the leader of the Mimbreno band. This relationship allowed Cochise to extend his influence over the Chiricahua Apache. His people remained at peace with white settlers through the 1850s, even working as woodcutters at the Apache Pass stagecoach station.

In 1861, the Arivaipa Apache band, unrelated to the Chiricahua, raided John Ward’s farm and fled towards the Chiricahua Mountains, Cochise’s territory. They took livestock and kidnapped Ward’s stepson, Felix. Lieutenant George Bascom was tasked with apprehending the raiders.

Bascom arranged a meeting with Cochise near the Butterfield Stage Station at Apache Pass. Cochise, accompanied by some family members, attended the meeting. Within his tent, Bascom accused Cochise of the raid. Cochise truthfully denied involvement but offered to help locate the culprits. Bascom declined Cochise’s offer, demanding the return of stolen property before releasing him. Cochise escaped by cutting a hole in the tent, and Bascom took his family hostage.

In the ensuing days, Cochise captured a wagon train and a Butterfield stagecoach, seizing hostages. Despite both parties seeking resolution, miscommunication and tensions hindered any agreement. Cochise attempted to negotiate an exchange with Bascom, but Bascom refused. As a result, Cochise executed his captives, and the soldiers retaliated by killing their Apache prisoners, including Cochise’s beloved brother, Coyuntura. This fueled Cochise’s grief and rage.

The Battle of Apache Pass: A Turning Point in the Conflict

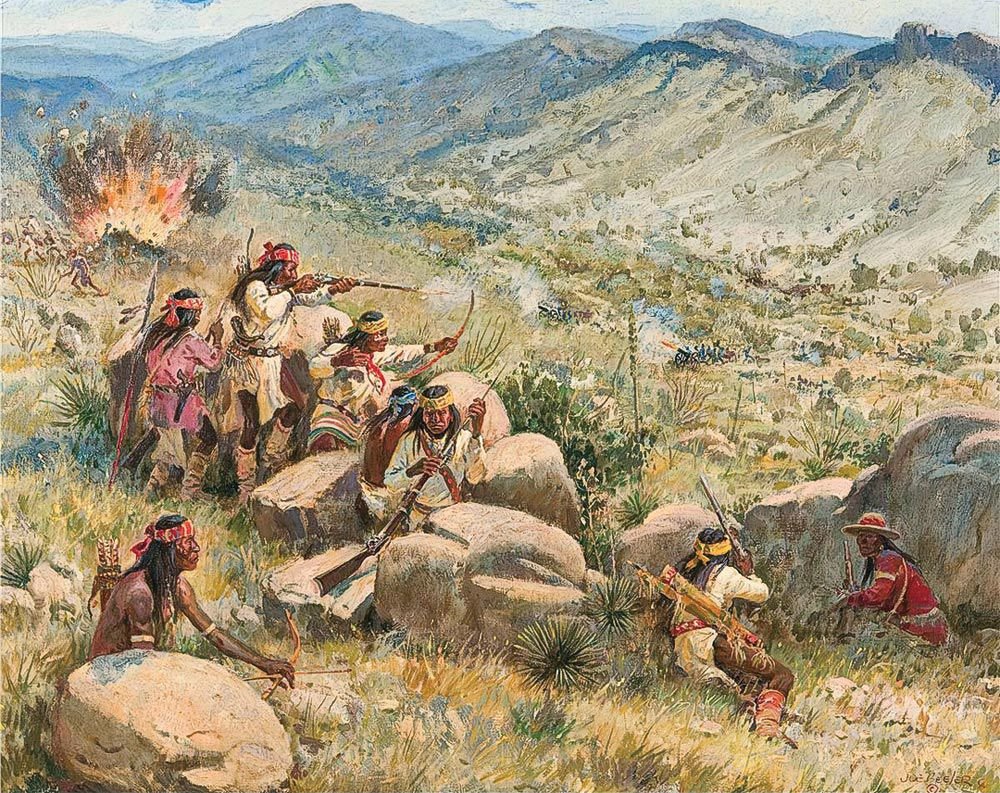

In 1862, a year after the Bascom Incident, Chiefs Cochise and Mangas Coloradas assembled the largest war party of the Apache Wars, consisting of approximately 200 warriors. Due to the ongoing Civil War, Union troops were stationed in the region to prevent the Confederacy from seizing the Southwest. On July 15, 1862, around 120 Union soldiers from the California Column, exhausted and thirsty, marched eastward from Tucson. They traversed Apache Pass towards Apache Spring near Fort Bowie, likely presenting an opportunity for the Apaches to plunder the military wagon train.

The Chiricahua attacked the soldiers from elevated positions, initiating the Battle of Apache Pass, one of the largest engagements of the Apache Wars. The Chiricahua’s success was hampered by the Union’s deployment of two Mountain Howitzer cannons.

In reference to the Mountain Howitzers, an Apache warrior remarked, “We would’ve won if you hadn’t fired wagons at us.”

Confused and overwhelmed by the cannons’ firepower, the Chiricahua dispersed and retreated. Mangas Coloradas sustained severe injuries during the battle, and his warriors carried him to Mexico, where they coerced a doctor into treating him.

In response to the battle, the first Fort Bowie was constructed near Apache Pass and Spring to secure the area against future assaults.

The Apache Wars, though long, were not fought in the manner of most wars. There were very few open battles. Ambushes were common. The Chiricahua did not consider retreat shameful, but a useful tactic. They would usually only engage in open battle if they had greater numbers, the higher ground, or the element of surprise. The Apache Wars lasted 24 years.

Chief Mangas Coloradas lost much of his will to fight after the Battle at Apache Pass. He was invited into negotiations at Fort McLane in New Mexico where he was killed. The loss of Chief Mangas led Cochise to take up leadership of the Chiricahua. Capturing or defeating Cochise now became the key to U.S. victory. Over a hundred years later, many Chiricahua people remember the Bascom Affair and the death of Mangas Coloradas better than the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Elusive Cochise: The Chiricahua Apache’s Natural Leader

Chief Cochise began to operate primarily from the impregnable mountain rock formation known as Cochise Stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains. Tall rock spires allowed lookouts to see anyone approach from far off. Many hiding spots allowed for easy ambush. The Stronghold was never taken. Cochise still ranged across a huge area–from Tucson, Arizona to Mesilla, New Mexico, and from Safford, Arizona to several hundred miles into Mexico. The United States military sought Cochise, but he proved far too elusive when chased, and far too effective a commander in battle. He was also unrivaled with a spear. The Chiricahua people were more adapted to the land, better at hiding in it, and had better knowledge of it than United States soldiers. The military had many fights with Cochise and the Chiricahua Apache, but no single fight ended the war.

The people of the United States did not understand Native American culture very well. They did not understand the separation between tribes. For example, they often thought the actions of one tribe were directly tied to that of another. This was rarely the case. Lieutenant Howard B. Cushing fell victim to this very ignorance. Cushing was attempting to pursue Cochise while another Chiricahua leader, Juh, (pronounced “who”) was pursuing him. Every time Cushing’s party got in skirmishes with Juh, Cushing assumed he was closing in on Cochise. However, he could not have been farther from the truth. Juh’s band eventually ambushed and killed Cushing.

General George R. Crook was raised on an Ohio farm. Uninterested in farming, he enrolled at West Point from 1848-1852 and graduated near the bottom of his class. After some success in the Civil War, he was hired to “fix the Apache problem.” He was a discreet and calculating man, speaking rarely and listening carefully.

Crook chose to ride a mule while in the Southwest. He felt it handled the heat and terrain better than a horse. He also developed the use of pack trains. Whether the task was battle or hard labor, Crook usually worked on the front lines with his men. Crook witnessed firsthand the ineffectiveness of the white man at tracking the Apache. He came up with perhaps the United States’ most effective strategy in the Apache Wars–tracking Apache with defected Apache. He would later recall his time in the Apache Wars as some of the most difficult work of his life.

Cochise’s Negotiation: The Creation of the Chiricahua Reservation

Finding or defeating Chief Cochise had proven futile for the U.S. Army. The strategy shifted to relocating him and the Chiricahua Apache to a reservation. Cochise was tired. He and his people had found life on the run and in hiding exhausting. The Chiricahua were very effective warriors. They were often able to take down many soldiers before falling. However, the U.S. had what appeared to be an inexhaustible supply of soldiers and provisions.

Chief Cochise was asked repeatedly to meet and discuss relocating his people to a reservation. He would always refuse because reservations at the time had poor conditions. The San Carlos Reservation, for instance, had bad water, rampant sickness, mandatory role call, and forced menial labor which the people believed beneath them as warriors. Cochise bided his time and continued to avoid capture and defeat.

In 1872, General O.O. Howard and Tom Jeffords, an Army scout, prospector, and employee of overland mail in Arizona, put their lives at risk by approaching Cochise Stronghold with few troops. When confronted by the Chiricahua, Howard and Jeffords told them they were not there to fight but to talk.

Cochise made Howard and Jeffords wait several days before granting them entry into his camp. Cochise held an audience with Howard and the two entered into reservation talks. Both sides were very stubborn but after some time Cochise got the upper hand. Cochise procured a reservation for his people that spanned much of modern day Cochise County in southeast Arizona.

The local newspapers slandered General Howard for giving up so much ground in the negotiations. Tom Jeffords became agent of the reservation. He would go on to become a Native American sympathizer, as well as the only white man Cochise ever considered a friend. On the reservation, the Chiricahua were able to roam free and camp wherever they wanted. There was no roll call taken. They were even allowed to leave the reservation, and often raided in Mexico, which stirred tensions.

The reservation brought about a peaceful period in the war which would last four years. Settlers did not approve of the reservation’s loose authority over the Chiricahua. In Washington, D.C., the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of War fought over jurisdiction of the reservation. Given the peaceful period, however, General Crook headed north to fight with Lieutenant Colonel George Custer in the Dakotas.

The Legacy of Cochise: A Prolonged Peace, but at a Cost

Cochise began experiencing intense stomach pains and could not always eat. In 1874, he died of what was likely stomach cancer. The whereabouts of his grave are still unknown, though it is thought to be somewhere in his Stronghold. Cochise was one of the Chiricahua’s most effective leaders during the time of the Apache Wars. He was the only one able to bring prolonged peace and freedom to his people, even if it did not last long after his death.

With Cochise’s death, the Chiricahua were left without a strong central leader. The U.S. government saw a chance to close the problematic Chiricahua Reservation. The final straw came when two Chiricahua warriors killed two white men for not selling them whiskey. The government fired Agent Jeffords and abolished the reservation.

Around this time, John Clum became agent of the San Carlos Reservation in east central Arizona. He was a notoriously pompous man. The Apache would nickname him the “Turkey Gobbler” because they thought he walked like a turkey. Clum travelled to the Chiricahua Reservation to order all the Chiricahua people to the San Carlos Reservation. He met with Cochise’s son, Taza, who had taken up the mantle of chief as his father had prepared him to do. Also at the meeting was Juh, whose brother-in-law often spoke for him because Juh had a stutter. Juh’s brother-in-law’s name was Goyakla. He would become known as Geronimo.

Goyakla to Geronimo: The Making of a Legendary War Leader

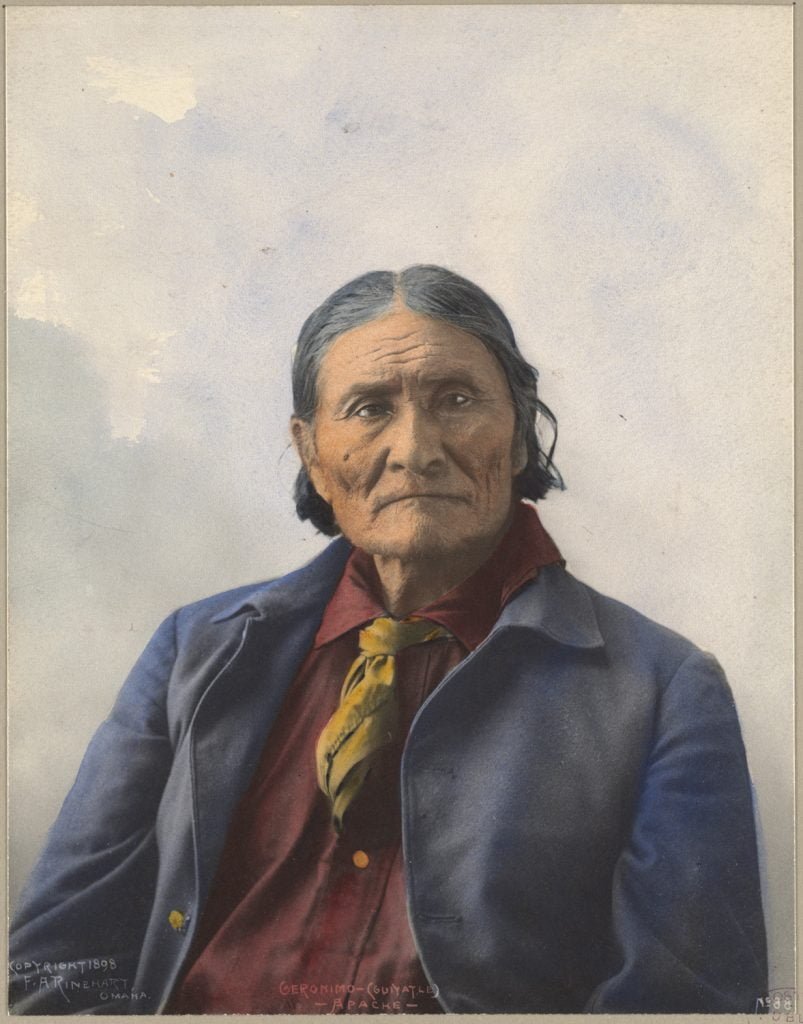

Geronimo was not a chief, but a medicine man of the Bedonkehe band of the Chiricahua Apache. He would eventually become their leader because he believed, like Cochise before him, that his people deserved freedom. Geronimo had been one of Cochise’s most devout warriors. He had helped him take captives after the Bascom Affair and had fought alongside him during the Battle of Apache Pass. Mangas Coloradas had been Geronimo’s chief, and Geronimo had been present at Mangas’ death.

Geronimo was born on the Gila River in New Mexico, not far from the Gila Cliff Dwellings. His birth name, Goyakla, meant “one who yawns.” He would go on to become a brilliant war leader. While Cochise was a noble leader, Geronimo was more of a rogue.

As a young man, Geronimo had lost one of his wives, some of his children, and his mother to a massacre carried out by Mexican soldiers. He would never forgive the Mexican people for this nor forget his hate for them. Geronimo felt he had little purpose after this event. One night, atop Bowie Peak, he heard Usen’s voice on the wind say to him, “You will never die in battle, nor will you die by gun. I will guide your arrows.”

Geronimo believed this to be true for the rest of his life, and for good reason. He petitioned to Chief Cochise and Chief Mangas to campaign deep into Mexico to avenge his family’s death. Geronimo told them he would lead the battle as he did not care whether he lived or died. It was during this campaign that Geronimo would get the name he is known by today.

The Turning Point: Geronimo’s Unrelenting Quest for Vengeance

During the battle, Geronimo did not fire arrows from cover as many of the other Apache did. Instead, he ran zig-zag at the Mexican soldiers so as not to be hit by their bullets. He would then kill them with a knife and take their rifles back to other Apache warriors, as he did not know how to use a rifle at this point. The Mexican soldiers began to shout “Geronimus!” Latin for Hieronymus, or St. Jerome, to warn each other of his charges. The Chiricahua Apache began to chant that name in enthusiasm and intimidation, “Geronimo!”.

Geronimo was a complicated man. Many Americans at the time dubbed him as “the worst Indian that ever lived.” He was quick-tempered and paranoid; nervous, but very, very lucky. He was deceitful and cruel, prophetic and brilliant, ambivalent and even sometimes a little sheepish. His contradictory yet effective nature makes him one of the most fascinating characters of the Apache Wars.

John Clum, agent of the San Carlos Reservation, struck a deal with Juh and Taza, who had taken his father’s place as chief. Juh and Taza agreed to gather their people and things, scattered throughout the now disintegrating Chiricahua Reservation, and move to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo instigated a disagreement between the leaders. Only one third of the Chiricahua went with Taza to the San Carlos. Two thirds followed Juh and Geronimo off the reservation, thus breaking the deal with Clum.

After arriving at the reservation, Taza ended up taking a trip to Washington, D.C. to learn about the ways of the white man. While there, however, he got sick and died. Chieftainship passed to his younger brother, Naiche, who Cochise had not groomed to be a leader the way he had Taza.

The broken deal infuriated Agent Clum. He received word that Geronimo was the instigator of the broken deal, and that he had made it all the way to the Ojo Caliente Reservation in New Mexico. Clum set out for the reservation at once. Geronimo must have not realized what danger he was in at the time. Geronimo was easily outsmarted and captured by Clum at the Ojo Caliente Reservation. This was due mostly to the Apache scouts who had betrayed him. Clum took Geronimo back to San Carlos where he hoped to put him to death, but Geronimo’s luck ran deep.

Back in Washington, D.C. the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of War were still fighting over jurisdiction of the Chiricahua Apache. They could not reach a decision on Geronimo’s fate. Clum was furious as Geronimo sat in shackles before his release. Geronimo stayed on the San Carlos Reservation for a few days, however. He decided to leave before his sentence could be finalized. Clum resigned shortly after Geronimo’s escape.

When Geronimo was captured on the Ojo Caliente Reservation, he accidentally brought the attention of the U.S. military to the Warm Springs band of the Apache who were living on the reservation at the time. They were led by Chief Victorio. The Ojo Caliente Reservation was closed, and Victorio and the Warm Springs band were ordered to move to the San Carlos Reservation, which they knew was far inferior to Ojo Caliente. Victorio and the Warm Springs band escaped in the night. An order was made, stating that any Chiricahua found off reservation was to be killed. The Warm Springs band were pursued across the Southwest and into Mexico fighting furiously the whole time. They were eventually killed by Mexican soldiers. Victorio was said to be the last one standing.

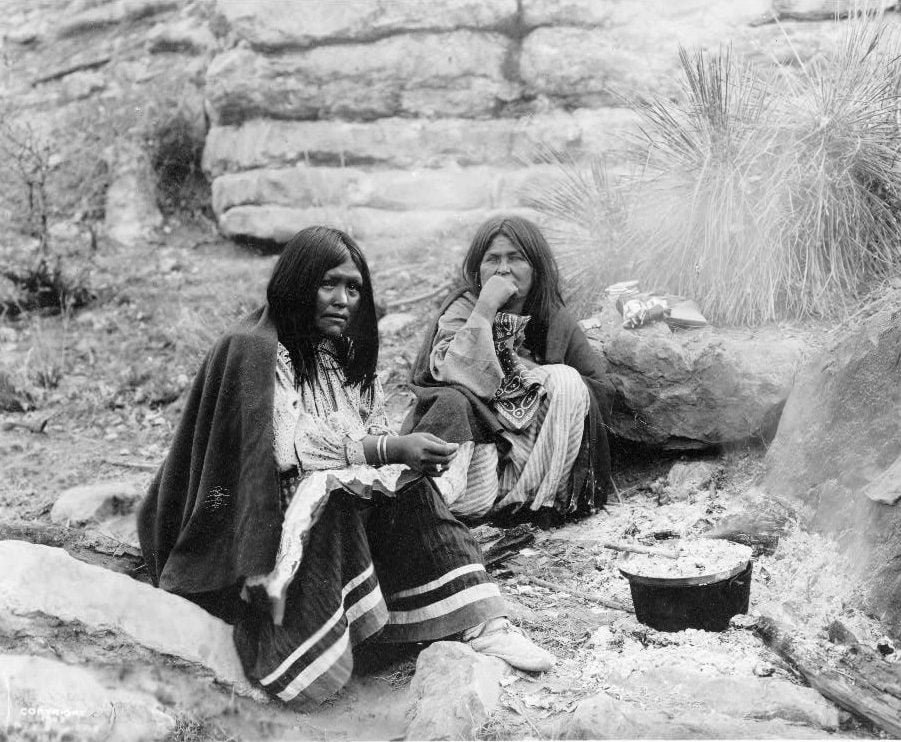

The Final Days of Chiricahua Freedom: A Desperate Stand in the Sierra Madre

Deep in the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico, in a place called Juh’s Stronghold, the Chiricahua Apache were beginning to gather in the largest numbers since the time of Cochise. Great warriors came, including the ironically named Fun, perhaps the best warrior of the group. Once Fun found himself surrounded by seven Mexican soldiers with only a bush to hide in. He killed each soldier with a bullet to the head and escaped with his life. Lozen, the famous woman who gave up a life of marriage to become a warrior, attended as well. There were also Chief Chihuahua and Chief Nana. Nana was a brilliant and shrewd leader who led some of the most successful raids even at 75-years-old.

The Chiricahua hid caches of food and supplies across much of the Southwest and Mexico. Geronimo trained young warriors. He despised the leaders of his people who gave up easily or made choices that led to their capture or death. Geronimo even went so far as to force Chief Loco and his band to depart the San Carlos Reservation at gunpoint, and it was a grueling journey. The Chiricahua at this point numbered around 600; half of what it had been at the beginning of the war in 1862. Juh unfortunately fell off his horse and died.

General George Crook returned to fight the Apache once again. His nickname, the Tan Wolf, came from the khaki-colored civilian clothing he wore. Chief Nana saw his return as good because he was a “good enemy.” Like Nana, Crook also had a strong respect for his enemy. When asked about the Chiricahua Apache he said, “Acuteness of sense, perfect physical condition, absolute knowledge of locality, almost absolute ability to persevere from danger. We have before us the tiger of the human species.”

Geronimo’s notoriety as a successful Chiricahua leader had grown. Crook knew that finding Geronimo would now be the key to U.S. victory. Crook set out with both Apache scouts and U.S. soldiers to do just that.

The Chiricahua continued to raid in both the United States and in Mexico. The Mexican people began to believe that Geronimo was the devil come to punish them for their sins. The U.S. and Mexico continued to track, capture, and kill Chiricahua Apache when they could. Deaths continued for both sides. The U.S. and Mexico struck a deal that they could cross each other’s borders in pursuit of the Chiricahua.

The Impact of Betrayal and Broken Deals on the Chiricahua Apache’s Fate

Only a few decades prior, the United States and Mexico had been at war, making the agreement rather unstable. Lieutenant Emmet Crawford was soon to discover this as he managed to locate Geronimo and his band in Mexico. One early morning, as they encircled Geronimo’s camp, the Apache horses sensed danger and began to bray, waking up the camp. A brief exchange of gunfire ensued, but no casualties occurred on either side and Geronimo and his band scattered into the nearby rocks. The soldiers were unable to distinguish between Apache allies and enemies, making them reluctant to shoot. Meanwhile, the Apache scouts, though firing, never seemed to hit their targets.

In 1892, an account of the scouts was penned by Lieutenant William E. Shipp of the 10th Cavalry, who led the scout companies. This account was later published in the Cavalry Journal.

“These men worked too hard and were too faithful under temptation to give any reason to suspect them of treachery. But it does not seem unreasonable to believe that they did not strongly desire the death of people belonging to their own tribe. They had not only been their friends, but some were relatives. Moreover, in their eyes, the hostiles had committed no crime, for they themselves had likewise been on the warpath. They wanted peace, but not at the expense of much bloodshed. The White Mountain scouts were too much afraid of their Chiricahua brethren to oppose them…“

Before Crawford could confront Geronimo and his band again, Mexican soldiers, unaware of Geronimo’s nearby whereabouts, accused Crawford of breaking the border deal. Crawford tried to reason, but the Mexican soldiers shot and killed him. Treachery was likely involved. Geronimo was rumored to have been sitting on a nearby hill, watching the events unfold, and laughing.

General Crook was hot on the heels of Crawford and was able track Geronimo down not long after Crawford’s death. Crook wanted to enter negotiations, but things were too tense at first. After a short skirmish, Geronimo and his band sat on a cliff above Crook’s company exchanging taunts with Crook’s Apache scouts. They entered into negotiations in a way no one could have predicted. Crook was a compulsive hunter, and the next day he wandered off on his own tracking an animal. Before long, he found himself alone face-to-face with Geronimo and some of his best warriors.

Geronimo didn’t kill Crook. He had found the same truths about life on the run as Cochise before him. The U.S. was too well-supplied, and had what appeared to be an endless number of troops. Constant vigilance and hiding was no way to live. The Chiricahua were of a low morale and wanted to enter negotiations. The Chiricahua respected Crook, and after some deliberating, they struck a bargain that the Chiricahua would move to a new reservation called Turkey Creek. Lieutenant Britton Davis became the agent.

Forced Assimilation: The Struggles and Rebellion of Chiricahua Apache on the Reservation

The war once again entered a peaceful period, however this one only lasted a year. Agent Davis tried to get the Chiricahua to farm. It was popular belief in the U.S. at the time that Native Americans would have to assimilate to the ways of the white man to survive.

Davis made it law that Chiricahua men could no longer beat their wives which within their culture was their right. Davis also made it illegal for the Chiricahua to brew the alcoholic beverage called Tizwin. One Chiricahua man was even sent as far away as Alcatraz for breaking these laws.

In 1885, Samuel Kenoi, a young Southern Chiricahua aged 10, had a father who belonged to Juh’s band. Later, in 1932, he shared his perspective on the Geronimo Campaign with anthropologist Morris Opler. During their conversation, he elaborated on the Apache’s viewpoint towards the white individuals who had confined them within the San Carlos Indian Agency.

“What they didn’t like was so much ruling; that’s what they didn’t like. They didn’t have all the Indians at the agency in those days. It was the people who lived around the agency, who saw white people all the time, who were controlled. The people out away from the agency were wild. That’s why some thought the white men had queer ways and hated them. After they got to know the white man’s way, they liked it. The white men gave them new things, new food, for instance. But it was the new-comers like Ho and Geronimo who didn’t like the white man. If there was any ruling to do, they wanted to do it.“

Unrest began to slowly brew on the reservation. It reached a boiling point as Apache translators began sowing seeds of tension between the Chiricahua and Agent Davis. One of these scouts was Mickey Free, who was once known as Felix Ward. He was the very same boy who had been kidnapped from John Ward’s farm in the raid that caused the Bascom Affair. Mickey was raised by Apache scouts but showed little allegiance to either the U.S. or the Apache. Mickey had been an Army scout and later an Apache scout. He understood both English and Apache, though imperfectly, so he served as a translator. Translations around this time were often more complex than English directly to Apache. Translations would often have to go from English into Spanish into Apache and vice versa. Miscommunication ensued.

Geronimo eventually heard a rumor that he was going to be arrested. He decided to instigate another breakout. Davis wired Crook, but it was too late. Carnage followed in the wake of the Apache escape from Turkey Creek.

Most of the Chiricahua remained on reservations this time. The remaining free Chiricahua took up hiding once again in the Sierra Madre Mountains. Crook pursued Geronimo into Mexico one last time. When he found him, Crook was upset with Geronimo for breaking all of their deals. Geronimo pleaded that he wouldn’t have broken the deals if he hadn’t heard that he was going to be arrested. Crook was not able to offer the terms of surrender that he was able to before. Geronimo knew his cause to be hopeless and surrendered once again.

Crook left for Fort Bowie, leaving the Apache removal in the hands of Lieutenant Marion Maus. That same night, Geronimo and his band bought whiskey from a Swiss bootlegger named Robert Tribolet. Tribolet supposedly profited from the Apache Wars and thus sought to perpetuate the war. He told Geronimo that, upon returning to Arizona, he would be hanged. In the days to come, in a drunken stupor, the Apaches escaped and broke the terms of their surrender. General Crook wanted Tribolet dead.

After this last failed surrender, General Crook contacted President Grover Cleveland. Crook told him he still wanted to offer the Chiricahua terms for their surrender. Cleveland rejected this, stating that the surrender needed to be unconditional. Crook disagreed with this method and felt that his way would bring about better results. Crook resigned and was not looked upon favorably afterwards.

A \$25,000 bounty was placed on Geronimo’s head and a new general took over: Nelson Miles. General Miles would earn little respect from the Chiricahua Apache. Unlike Crook, Miles lead from faraway forts. Miles also came up with a shrewd and cruel idea that would bring about a final Chiricahua surrender.

Fear gripped the Southwest during the final summer of Chiricahua freedom in 1886. Geronimo led through Naiche, who was still chief. The final free band of Chiricahua numbered only 37. They included 18 warriors, 13 women, and six children including two infants. They remained at large for five months while around 5,000 employees of the United States Army (a quarter of the force) were stationed in the area to track the Apache. Around 3,000 Mexican soldiers and a little less than 1,000 volunteers were also put to the task.

Some of the women and children in the final Apache band surrendered as the summer wore on. The band only experienced one death that whole summer. Many U.S. soldiers found conditions in the Southwest during summer to be unbearable. Meanwhile, Geronimo was more reckless than ever. He felt it was the best fighting the Apache had ever done. He was also said to have trusted in his powers more than ever. When a Chiricahua encampment was found, he was supposedly able to intuit the situation from miles off. The Chiricahua spent most of their time during that summer in Mexico.

The last six years of the war had cost the lives of 319 Americans and 682 Mexicans.

There were still 434 Chiricahua living on the San Carlos Reservation. Miles’ idea was to banish all of them to prison thousands of miles away in Florida. The free Chiricahua remaining had close family members in this group. Miles hoped that knowing they would never see their families again without surrendering would cause a final Chiricahua Apache surrender.

Geronimo’s Final Stand

Late that summer in 1886, Lieutenant Charles Gatewood pursued Geronimo and his band deep into the Sierra Madre. At a place in the mountains called Bavispe, he knew he was closing in. Gatewood sent two Apache scouts forward who some of the free Chiricahua band had personally known. The scouts told Geronimo and his band that the rest of their people, including their families, had been sent thousands of miles away. This had the intended effect. Geronimo held a conference with Gatewood and agreed to surrender.

In Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Geronimo is alleged to have said: “Once I moved about like the wind. Now I surrender to you and that is all.”

Geronimo’s last of four surrenders took place in Skeleton Canyon, southern Arizona, in the summer of 1886. General Nelson Miles claimed victory, but the surrender was fraught with controversy. It was agreed that the Chiricahua Apache would reunite with their families in Florida, but President Grover Cleveland anticipated an unconditional surrender. Unknown to the Chiricahua, Miles had deemed all previously agreed terms void, as Geronimo had broken them all. Both Miles and Cleveland acted within the framework of broader U.S. policies aimed at quelling Native American opposition and assimilating their communities. The government never intended for the Apache to reunite with their families in Florida.

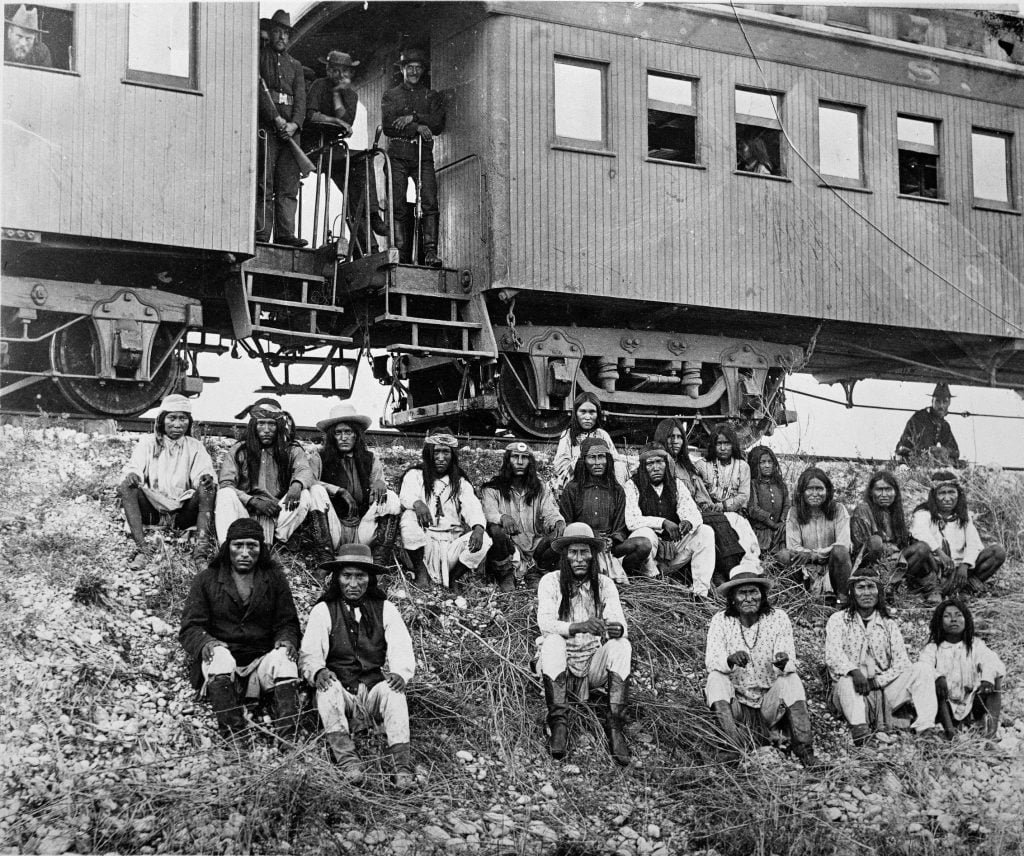

Geronimo and his followers were taken to Fort Bowie, where he drank from Apache Spring for the final time. He had fought alongside Chief Cochise at the Battle of Apache Pass, 24 years earlier. At 65 years old, Geronimo took his final steps on native soil and boarded a train to Florida for the first time. The U.S. government had ultimately resolved the “Apache problem.”

Journey to Florida and Incarceration

During the train journey to Florida, Geronimo’s band feared they would be killed at any moment. Upon arrival, they were not reunited with their families at Fort Marion as promised but taken to Fort Pickens. They would only see their families more than two years later, breaching Miles’ surrender terms. Many Chiricahua died of malaria while in captivity, and Geronimo’s daughter was born, unbeknownst to him.

The Chiricahua Apache, suffering from malaria, were moved from Florida to Mount Vernon in Alabama as prisoners-of-war. In this alien landscape, their children were sent to Pennsylvania schools to learn Christianity, English, and other aspects of American life. Many children contracted tuberculosis and died, prompting Chiricahua parents to hide their offspring. After two years in Florida, Geronimo and his band moved to Alabama and finally reunited with their families.

General Crook visited the Chiricahua in Mount Vernon, but having lost respect for Geronimo, he met with other leaders instead. Crook condemned the Pennsylvania schools and proposed relocating the Chiricahua to Fort Sill Reservation in Oklahoma, a more familiar environment. Crook died two months later.

After eight years as prisoners-of-war, only 119 Chiricahua were left when they moved to Oklahoma. There, they could once again hear coyotes howl and gather their cherished mesquite beans.

“Worst Indian of All Time”

Geronimo, once dubbed the “worst Indian of all time,” became one of the most famous. His exploits were greatly exaggerated and celebrated worldwide. He traveled the nation, performing at fairs and exhibitions like the Buffalo Bill sideshow, and selling small souvenirs such as coat buttons.

Geronimo even participated in Teddy Roosevelt’s presidential parade, attracting more attention than Roosevelt himself. Geronimo asked Roosevelt if his people could return to the Southwest, but Roosevelt refused due to lingering animosity towards the Chiricahua.

Encouraged by settlers, Geronimo attempted to embrace Christianity in his later years but struggled to forgive himself for the lives he had taken, particularly children’s.

An artist who painted Geronimo claimed he had over 50 bullet wounds, though this is difficult to verify. Geronimo allegedly stated, “Bullets cannot kill me,” and indeed, they did not. In 1909, he fell from his horse into a ditch after a drinking spree, contracted pneumonia, and died soon after, reportedly regretting his surrender.

Aftermath for the Chiricahua Apache

In 1913, after 27 years in captivity, the Chiricahua were finally released and no longer considered prisoners-of-war. One-third chose to remain at Fort Sill, while two-thirds relocated to the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico. During Chief Cochise’s time, the Chiricahua Apache numbered 1,200. By the end of the war in 1886, they had dwindled to 500, and upon their release, only 261 remained. Today, over 850 Chiricahua Apache exist, with descendants of Cochise and Geronimo still living among them.

Despite dedicating a significant portion of his life to battling Native American tribes, General George Crook, in his final years, had become an advocate for the rights of Indigenous peoples and openly condemned the numerous injustices inflicted upon the Apache.

“The buffalo is all gone, and an Indian can’t catch enough jack rabbits to subsist himself and his family, and then, there aren’t enough jack rabbits to catch. What are they to do?”

In summary, Geronimo’s ultimate surrender signaled the end of a tumultuous era for the Chiricahua Apache tribe. Their experiences during and after captivity highlight the intricate relationships between the U.S. government and Native American tribes. Geronimo’s life serves as a potent symbol of defiance and adaptation, but it is crucial to understand his story within the larger context of the struggle for survival faced by the Chiricahua and other Native American tribes during this period.

Suggested Further Reading:

- Basso, Keith, ed. (1971). Western Apache Raiding and Warfare from the Notes of Grenville Goodwin. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Debo, A. (1976). Geronimo: The man, his time, his place. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Kraft, Louis (2000). Gatewood & Geronimo. Albuquerue: University of New Mexico Press.

- Opler, Morris E., ed. (1973). Grenville Goodwin among the Western Apache. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Turcheneske, John Anthony Jr. (1997). The Chiricahua Apache Prisoners of War: Fort Sill 1894-1914. Niwot: University Press of Colorado.

- Utley, Robert M. (1977). A Clash of Cultures: Fort Bowie and the Chiricahua Apaches. Washington DC: National Park Service.

- Worcester, Donald E. (1979). The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.